Telomeres & Epithalon

Introduction to Telomeres

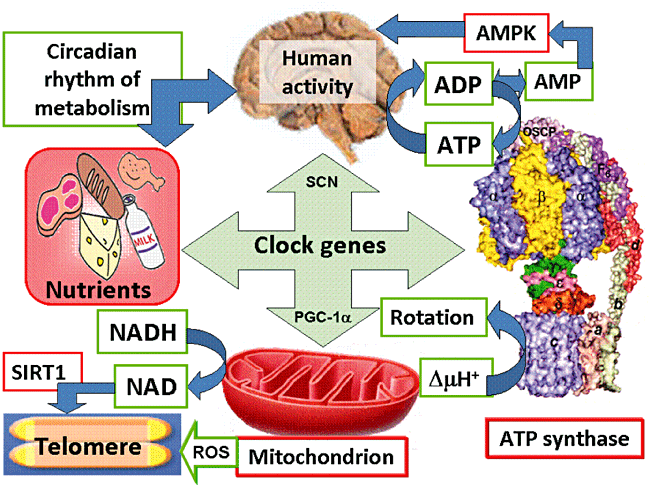

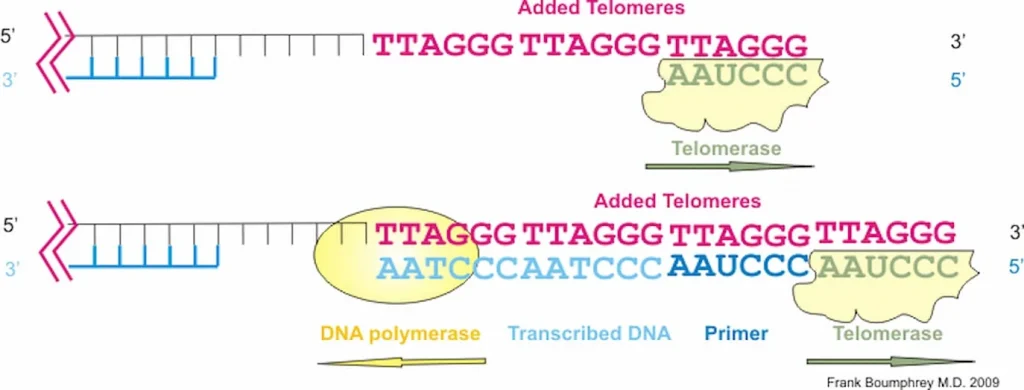

Telomeres are repeating sequences of nucleotide sequences (TTAGGG) that tag the ends of all chromosomes. They are designed to prevent unpredictable changes in the DNA strand, keeping the genome stable.

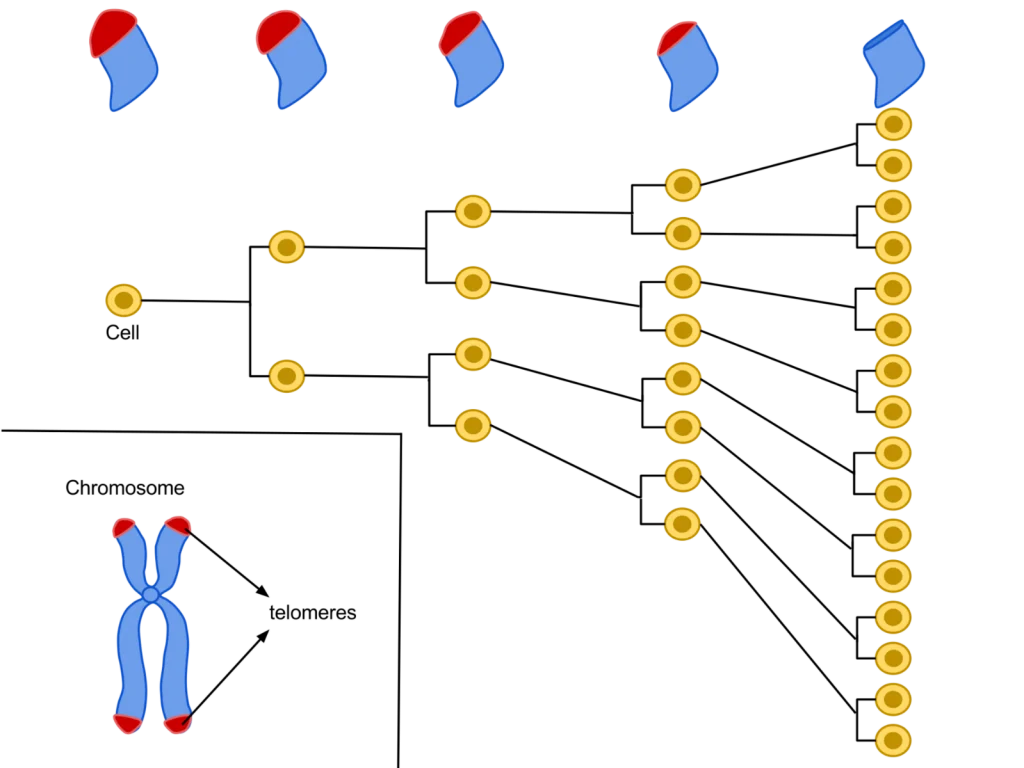

Their primary function is to prevent chromosomal “fraying” when a cell replicates, much like the plastic tips on the end of shoelaces. As a cell ages, its telomeres become shorter.

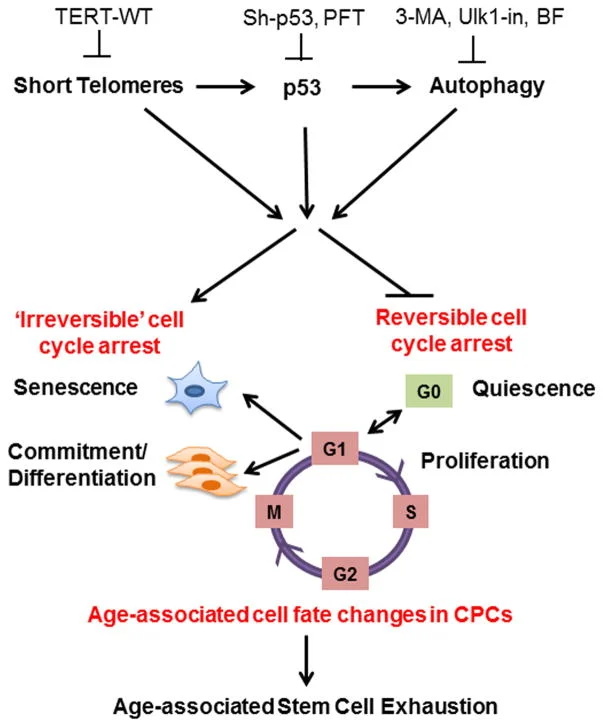

This shortening is thought to be one of several factors that causes cells to age. In actively dividing cells, such as those in the bone marrow, the stem cells of the embryo, and germ cells in the adult, telomere length (TL) is kept constant by the enzyme telomerase.

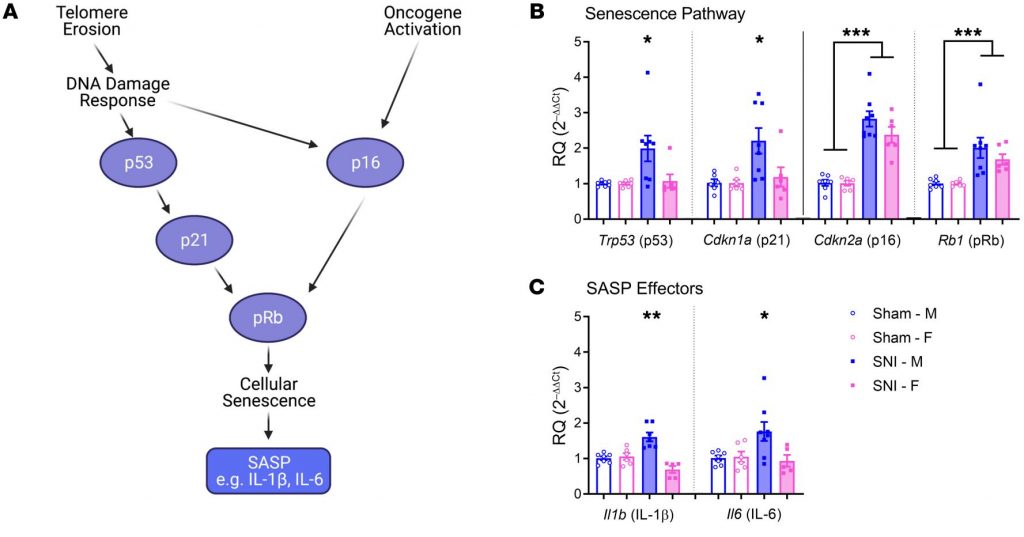

As the organism grows, this enzyme becomes less active over time. This leads to a slow decrease in telomere length, until a point is reached at which the cell is no longer capable of replication (‘replicative senescence’). A cell can no longer divide when telomeres are too short—once they reach a critical point, the cell becomes inactive (or ‘senescent’), slowly accumulating damage that it can’t repair, or it dies.

What is Epithalon?

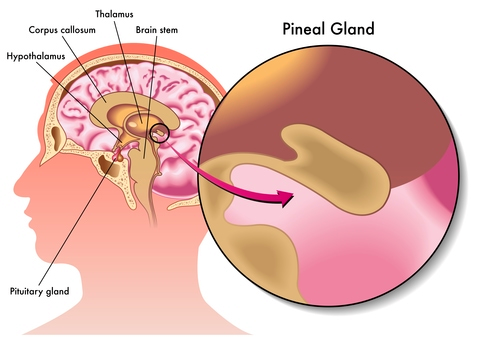

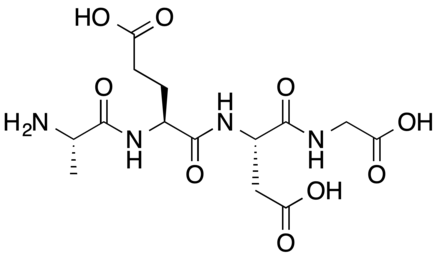

Epithalon (aka Epitalon) peptide (Ala- Glu-Asp-Gly) was constructed and synthesized based on amino acid composition of Epithalamine, a complex peptide preparation isolated from animal brain pineal. It was first discovered in the late 1980’s by Prof. Vladimir Khavinson from The Sankt Petersburg University, Russia.

As the most prominent tasks of the pineal gland are to maintain different kind of processes in our body, such as to normalize the activity of anterior pituitary and to maintain the levels of calcium, gonadotropins, and melatonin, its activity is highly regulated by a series of feedback mechanisms. Epithalamin acts as an antioxidant and increases the resistance to stress and lowers the levels of corticosteroids. The life extension and anti-aging properties, amongst a variety of different clinical indications, of epithalon are incredible antioxidant and increases the resistance to stress and lowers the levels of corticosteroids. The life extension and anti-aging properties, amongst a variety of different clinical indications, of epithalon are incredible.